All the world's futures

„A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.“ (Walter Benjamin, Theses on the Philosophy of History, 1940)

In your curatorial statement you quote Walter Benjamins "Theses on the Philosophy of History". He wrote the essay under the threat of National Socialism, so his conception of the future was very pessimistic. Why are his theses, especially his description of Paul Klees Angelus Novus, the “angel of history”, at the core of your concept for the Biennale?

O.E.: It was bleak, of course. His notion of future was very bleak. There are many important and true thoughts in this essay. Benjamin quotes Marx and Hegel, saying that great historical facts and personnages recur twice. He forgot to add: once as tragedy, and again as farce. Or: The tradition of the oppressed teaches us, that the “state of emergency” in which we live is not the exception but the rule. (laughs) I don’t wont to quote the entire thing now. But I think it is really important to engage with the fact, that Angelus Novus was a painting that was made by Paul Klee after the First World War. So this question of an allegorical reading of Klee's Angelus Novus is enlightening. Benjamin knew in anticipation what was going on during his time. And that’s what I find incredibly productive: in seeing how this depiction of catastrophe really can also be anticipated. We have many, many different catastrophes going on. And most of the works in the exhibition have to be read under this view of the catastrophe.

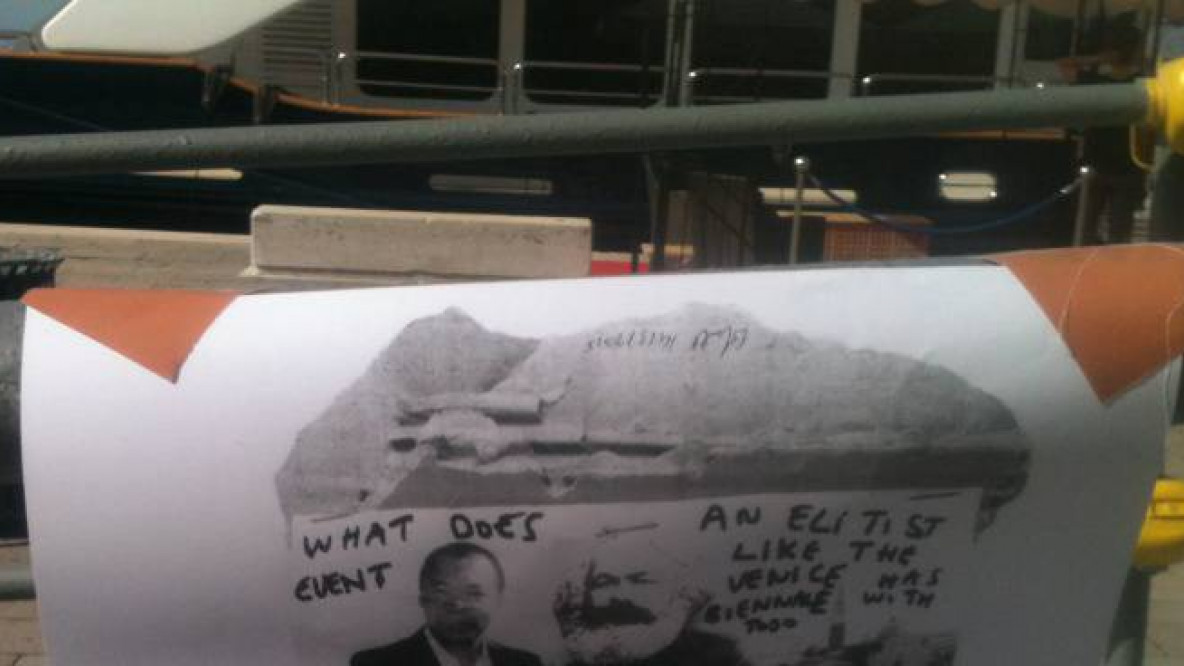

If we see the Biennale as part of the art system which is highly capitalised, don’t you think it is a bit cynical to stage "Capital" by Karl Marx?

O.E.: On the contrary. Ideas have lives and ideas also are autonomous. In this sense reading "Capital" within the context of the Biennale is something that is quite powerful. I think the point is that we often tend to infantilize art. We think that art should really behave, not disturb, you come to enjoy it and so on and so forth. So in my view what is essential to underscore: the art system is a complex system and the genetic code of the Biennale is very much imbedded in the art system. It cannot function different and I think we need to think a little bit more precise about the collision of context within the art system. The market is not the monster we often make of. It exists and we have to recognize it. And recognizing means that we really formulate a response to it and not to pretend that it doesn’t exist. And the Biennale is a very special withdrawal from the market, at the moment I think. That’s also why I have chosen a lot of very little works in the exhibition. It might not be so clear immediately. But you know - small pictures, very few monumental things.

Marxism, Neo Marxism is very vivid at the moment. If you look at what is happening in Greece for instance…

O.E: Of course, I have been looking at it for a very long time. Eisenstein, Marx all this thinkers are present in the exhibition. And then you look at the work of the artists in the exhibition: Isaac Juliens film "Capital", Alexander Kluges "News from Ideological Antiquity", which he reedited for the Biennale. It is all over the place and it is really quite powerful to see the ongoing analysis of these systems of production and accumulation and circulation with which the artists have been engaged and which we are trying to present. For example also Chris Markers "Le Joli Mai". All of these works show very clearly that artists have been addressing these questions in very critical ways. So it's not just Syriza, or the current context of struggle within the European economic landscape, but I think it is also the struggle about underscoring the tension between capital and the states form, which we see in Greece, which is imbedded right there.

Ghanaian/British architect David Adjaye designed the "Arena" in the Padiglione Centrale. What is its role?

O.E.: The arena is a gathering place. A place of our common work and it’s a place of animation. It’s a place of the voice, the art of the song. You know readings, lyrics, scripts, recitals, performances and debates. That's its role. It is really a space of annotation of the entire exhibition. It is part of the central nervous system of the exhibition.

What would you like people to take with them, having seen the exhibition?

O. E.: The vitality of the work of imagination that the artists propose.

Born in Nigeria in 1963, Okwui Enwezor is a curator, art critic, editor and writer; since 2011 he has been the Director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich. He was Artistic Director of the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale in South Africa (1996-1998), of documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany (1998-2002), the Bienal Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo de Sevilla in Spain (2005-2007), the 7th Gwangju Biennale in South Korea (2008) and of the Triennal d’Art Contemporain of Paris at the Palais de Tokyo (2012). Enwezor’s wide-ranging practice spans the world of international exhibitions, museums, academia, and publishing. In 1994 he founded “NKA: Journal of Contemporary African Art” published by Duke University Press. He is the author of numerous essays and books, among others: Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art (2008).

Acconsenti per leggere i commenti o per commentare tu stesso. Puoi revocare il tuo consenso in qualsiasi momento.