When movies (re)build bridges

-

This article was published in Italian with the headline Se il cinema (ri)costruisce ponti. As the interview was conducted in English, we publish the English version as well.

-

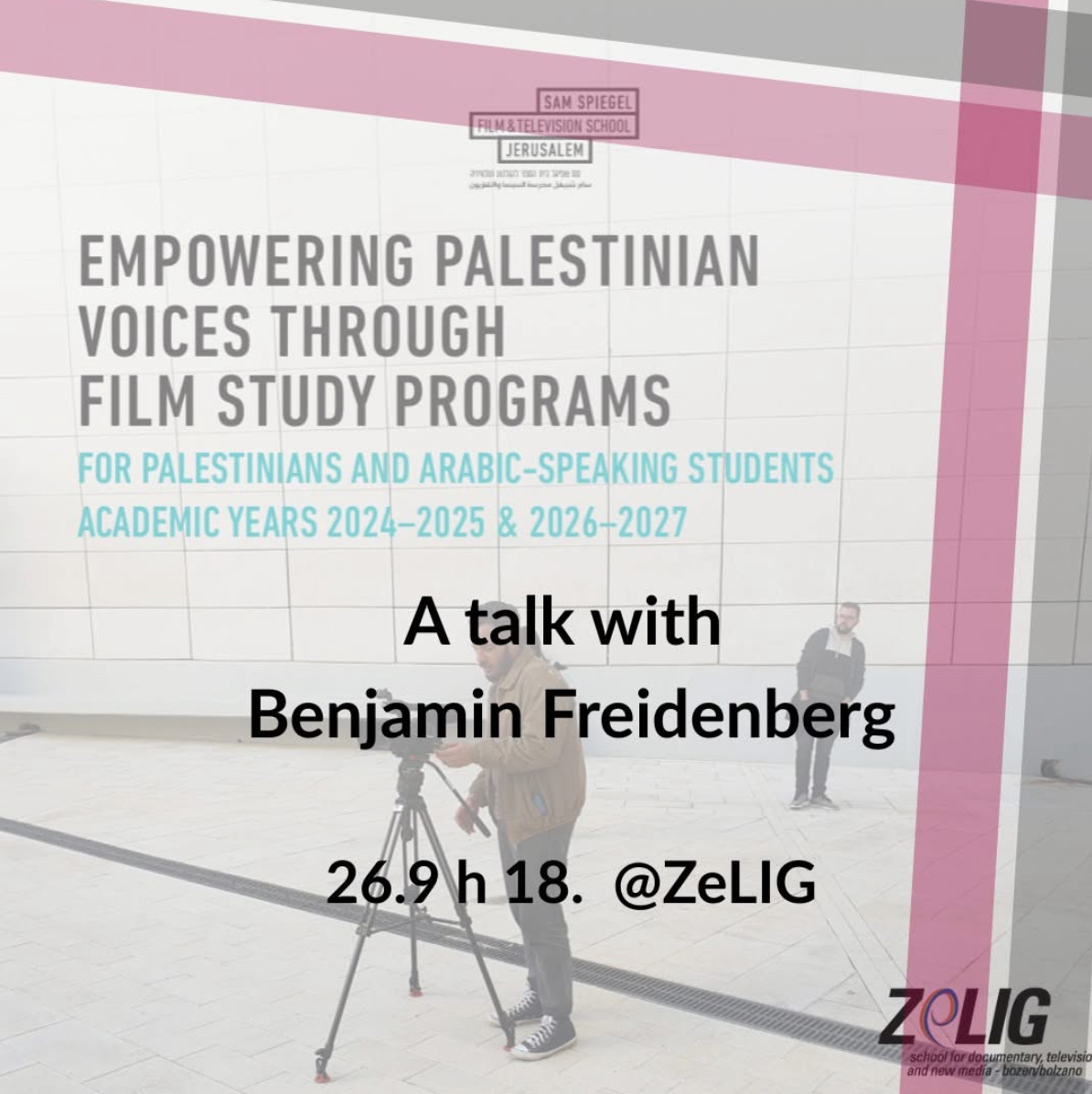

For more than two decades, Benjamin Freidenberg has worked in the art world at the intersection of creativity, activism, and education. At the core of his efforts is a commitment to creating jobs, opening opportunities for artists, and fostering dialogue through collaboration. He recently visited the Zelig School for Documentary, Television and New Media in Bolzano, where he presented his work as director of the Arabic-language programs of the Sam Spiegel Film School in Jerusalem. Together with Dana Blankstein Cohen, then the newly appointed director, he developed initiatives aimed at making film studies accessible for Palestinian students and refugees, fostering and facilitating platforms for Palestinian talents to tell their own stories through cinema.

The school carries the legacy of Sam Spiegel, the renowned Hollywood producer who had been head of marketing at Universal Studios in Berlin during the 1920s, working alongside directors such as Otto Preminger and Billy Wilder, before fleeing Germany during the Nazi era. One of his last wishes was to see a film school established in Jerusalem. His legacy includes producing classics like Lawrence of Arabia and On the Waterfront, but for Freidenberg, it also represents a story of exile and displacement.„Sam Spiegel, the producer, experienced the tension between the place you work in and the place you have to flee,“ he reflects. „Also, all his films voiced the experience of the immigrant, the other and the importance of dialogue between people. His legacy—sensitivity to others, creating a platform for art and free speech—is especially vital now, when free expression is under threat.“

Although the school itself was founded in 1989, its Arabic-language programs only began in 2021 when the newly appointed CEO of the Sam Spiegel Film School, Dana Blankstein-Cohen, invited Freidenberg to launch the programs. The absence of structured programs in Arabic underscored the challenges ahead: language barriers, cultural gaps, and generational divides. Freidenberg points out that his generation grew up when there was more contact between Israelis and Palestinians, and they knew each other’s languages and cultures. Today’s younger generations often lack that exposure.

-

The power of storytelling to transform societies

The Study Programs in Arabic include multiple initiatives, from a one-year pre-college program offering scholarships, workshops in film craft, masterclasses, and cultural tours, to training film courses in Palestinian populated cities and an upcoming two-year professional filmmaking programs in Jerusalem and Haifa, training 40 students annually in directing, screenwriting, cinematography, and production. The program also reaches more than 500 high school students across East Jerusalem and refugee camps, introducing them to storytelling, cinematic heritage, and opportunities in film. The study programs were open 3 years before October 7 and continue to offer higher education in the arts and filmmaking.

What is often overlooked in international reporting is that Jerusalem itself is surrounded by areas of acute hardship, including several refugee camps, Freidenberg observes. „The Shuafat Refugee Camp, for example, lies just a few kilometers from the city center. Established in 1965, it is the only Palestinian refugee camp within Jerusalem’s municipal boundaries and is home to more than 30,000 residents living in extremely dense conditions, with poor infrastructure and limited access to municipal services. Despite being under Israeli jurisdiction, the camp suffers from systemic neglect, overcrowding, and frequent clashes. For many young people growing up in Shuafat and other nearby camps, opportunities for cultural expression and professional development are rare, which makes the creation of educational and creative frameworks not only necessary but transformative“.

These programs also provide structured language instruction in Arabic, Hebrew, and English, mental health support, and cultural competence training for faculty. As Freidenberg notes, „It’s not only education. It’s an ecosystem—one that creates work, fosters dialogue, and nurtures the next generation of Palestinian storytellers.“

„It is important for me to stress that the study programs are led first and foremost by Palestinian filmmakers and lecturers, whose knowledge and artistic vision shape the content and the spirit of the work,“ Freidnberg says. „Unfortunately, due to the current political climate and real threats they are exposed to, their names cannot appear publicly. Palestinian creatives and filmmakers can and should speak for themselves — their voices do not require mediation or empowerment from others. I strongly oppose the patronizing local and international voices that presume to speak over Palestinians and their storytelling, instead of listening to them directly. My role is not to represent them, but to remain behind the scenes and ensure that the programs can operate and flourish despite the many obstacles“.

At the same time, the Sam Spiegel Film School team is launching the In Conflict: International Documentary Film Lab, an annual nine-month program that will be taking place in several international locations, dedicated to developing films that grapple with conflict in all its forms—regional, political, internal, and interpersonal. This will be an additional endeavor to the existing Film & Series Labs, which their director, Mor Eldar, currently leads.

Open to filmmakers worldwide, the lab selects ten projects each year. Participants receive mentorship, attend workshops and masterclasses, and develop their films across four sessions—two in Jerusalem, and two in conflict-related sites abroad. Projects receive production grants, logistical support, and are showcased before international producers and funders.

Open to filmmakers worldwide, the lab selects ten projects each year. Participants receive mentorship, attend workshops and masterclasses, and develop their films across four sessions—two in Jerusalem, and two in conflict-related sites abroad. Projects receive production grants, logistical support, and are showcased before international producers and funders."

-

Cinema fosters empathy

In the wake of the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent war in Gaza, the political climate has grown increasingly fragile, making these challenges even more difficult, as divergent narratives can easily spark new tensions. Yet Freidenberg insists that breakthroughs are possible.

„Our students—Israeli and Palestinian—are learning to listen to each other, even when they don’t agree, even when they carry different griefs, beliefs, and narratives,“ he says. „That’s what we aim for: to educate them to be worthy filmmakers who can listen and create.“

For him, cinema goes beyond reportage or social media—it is about complex stories, fictional characters, and reflections of reality that invite empathy. „This is what we’re working on, and it’s not easy — it’s never easy — but that’s the beauty of film. From my experience, film and the arts are much more successful at bringing people together than religion or diplomacy. And you know, with my 20 years of experience, I truly believe in what we do. Even if it’s on the small scale of a film school and not for the masses, every film is like a megaphone for humanity and its stories. Giving voice to Palestinian narratives, at this time, is something we feel is not only a human responsibility but also a creative one.“

Such work is not without its logistical difficulties. For Palestinians living beyond the separation wall or in refugee camps, attending classes in Jerusalem can mean long journeys, often involving multiple checkpoints. But with programs in East Jerusalem, Haifa, and Palestinian-populated cities in Israel, the school continues to expand access despite obstacles.

„Film production is always complicated,“ he adds. „We’re production people. We come up with solutions. Even if the situation in the Middle East gives us little reason to be optimistic, we remain very optimistic about film, about our students, their projects, and their futures.“

For Freidenberg, raising awareness outside the region is not simply about recognition but about responsibility. „This work shouldn’t just be ours alone,“ he says. „It should be an international endeavor.“ The upcoming anniversary of October 7th brings painful memories. Freidenberg personally knew hostages murdered in Gaza and people killed in Israel that day. He also knew applicants from Gaza who had applied to the school in 2021 and 2022—some of whom are no longer alive, some who fled, and filmmakers who were killed in bombings. „It’s about people. I see both. I see the grief and sorrow of both peoples. And I wish that Israelis and Palestinians could also see that. But we know the power isn’t equal. And what the Israeli government is doing now destroys bridges that once existed,“ he says.

-

Solidarietà con Gaza, voce al dissenso israeliano

While traveling in Europe, Freidenberg has noticed the growing solidarity with Gaza. He does not see this as a threat but as an understandable reaction. What he wishes, however, is for solidarity to become action.

„Supporting Palestinians shouldn’t just be about feeling moral or good about oneself. It must be an active responsibility to make things better. Some people say, ‚We won’t collaborate with Israeli institutions, especially in culture.‘ But boycotts don’t help Palestinians. They may make people feel good, but they don’t change anything on the ground. Especially not for an institution like ours, which is committed to making education accessible, even now.“

For him, engaging with Israeli dissident voices is also essential. „Without collaborating with dissident voices from Israel, no change can be vehicled and performed. Israeli dissident voices and activists often fill the void of international aid and field organizations in Palestine, not only because it’s our responsibility but also because there’s no one else on the ground to do the work we do with our Palestinian allies and partners.“

He is adamant that cultural boycotts often harm the very communities they aim to support. „A boycott that diminishes any chance for dialogue and future-building hurts the Palestinian people first. ‚Free Palestine‘ cannot be an accessory for moral and democratic values. It should carry a responsibility and active endeavors to establish a future for the people who need it most, considering also the existence and shared living of both people—Israelis and Palestinians alike.“

Independent, non-governmental, civil, and cultural actions, he argues, „can be more powerful and impactful than one thinks.“

Hi recent visit to Bolzano left a deep impression. „To learn about this very special place, its history of conflicts and current politics, was meaningful from my perspective, where two peoples live in one land. It’s hard to be hopeful, but one must be. For me, it was emotional and educational, to learn from your past and to see the current reality. Even on a micro level, it gives hope.“

For Freidenberg, that micro-level hope is sustained through film. Every project, every student, every story told becomes a megaphone for humanity—a way of voicing grief, resilience, and the possibility of dialogue in a fractured world.

*The article was updated on October 10 to clarify the situation in refugee camps around Jerusalem and the role of Palestinian filmmakers and lecturers in the Arabic study program.

-

Weitere Artikel zum Thema

Chronik | SALTO changeA Gaza è in corso (anche) un mediacidio

Politik | Gaza-Krieg„Es gibt kaum einen Ausweg“

Gesellschaft | L'intervista“A Gaza anche la speranza è malnutrita”

Stimme zu, um die Kommentare zu lesen - oder auch selbst zu kommentieren. Du kannst Deine Zustimmung jederzeit wieder zurücknehmen.