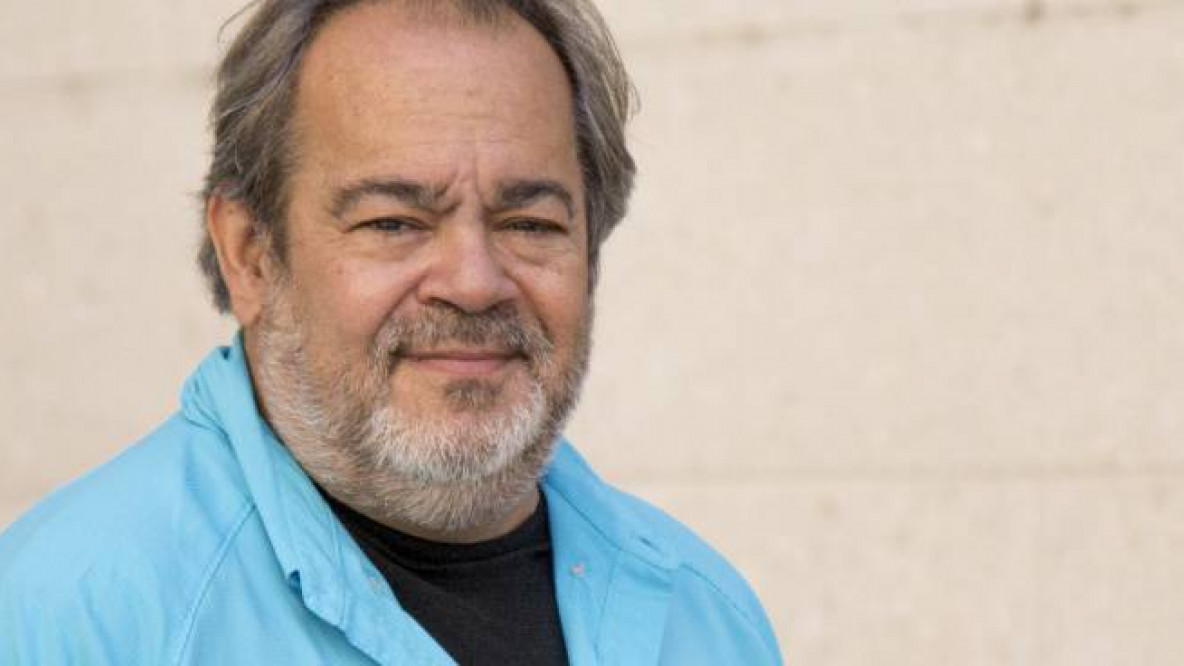

(Citizen) Journalist

A visiting speaker at unibz’s Dies Academicus in April, the distinguished American journalist took time out to speak with Academia about how the digital revolution is busting open his field, and why Las Vegas is still the most honest burg on the planet.

Interview by Sigrid Hechensteiner and Arturo Zilli*

Technology has enabled the average citizen to report news like journalists do. Who qualifies as a journalist these days?

Cooper: I’ve been exposed to some really stupid debates, I mean, really stupid, like: “Who’s a journalist and who’s a blogger?” Shit like that. To me, when it comes to information,

I don’t care who’s a journalist or who isn’t a journalist. I’m interested in people who commit acts of journalism.

You've always been able to commit an act of journalism as a human being. Now it’s easier.

So should we stop talking about journalism as a field then?

Cooper: There’s always going to be people that do the work that journalists do now… but the institutions of journalism are collapsing. The nature of news and the nature of journalism [have changed] because the relationship people have to the means of communication has completely changed.

How so?

Cooper: For those people who are journalists… there are two principles they have to you understand in the digital world as it exists today: First, the audience knows more than you do. They’re not smarter than you necessarily (some of them are), but they necessarily know more than you do—which means your relationship with them must change: it cannot be unilateral. The second thing is that the audience is no longer the audience, but those formerly known as the audience, as J. Rosen from NYU says. [Editors’ note: Rosen’s 2006 article “The People Formerly Known as the Audience” describes the modern media audience as frequent creators of their own news content.] And anyone who continues to treat the audience as ignorant, as unilateral, is out of the game.

Is there any future for print news then?

Cooper: People who tell you that newspapers are going to survive and that the basic system will survive, they’re lying to themselves and they’re lying to you. It’s not true. They’re dead. Their primacy is directly challenged now, and they have absolutely no traction among this generation.

But don’t we risk losing something important if these time-honoured institutions fail?

Cooper: The media generally has a much more inflated view of itself than it deserves. What has it produced in the last 200 years? After tens of thousands of books and millions of newspapers professionally produced and hundreds of millions of dollars spent on electronic communications, most Americans don’t know where Italy is on the map, let alone what ISIS is or what a Shia or what a Sunni is. I get very frightened when good-thinking people say, “If we destroy these journalistic institutions, how do we know who we’re going to trust?” What they’re really saying to me is, “How can I not take responsibility? How can I be handed something that is verified so that I don’t have to do anything?” It makes no sense. If you go to the library… there’s no one to tell you which [book] is the truth—that’s your problem.

But if everyone can be a journalist, and news is freely available on the Net, who’s going to pay for it?

Cooper: You know what, I don’t know. Maybe communities will pay journalists… maybe people will raise money collective through the Internet to pay journalists. I see absolutely nothing noble or positive in the commercialism of news… up till now, it’s only been a negative force. So I’m on the other side of the debate. Maybe we shouldn’t [pay journalists]. Maybe it’s more important to have very good news produced by communities of people and not have professional journalists who are susceptible to bribery and have to please their advertisers. Journalism should not exist to provide 50,000 jobs: it’s more important than that.

Do you have any business models to suggest?

Cooper: After the printing press was invented, it took 150 years for somebody to say, “Oh, let’s do a newspaper!” So if you'd asked someone 50 years after the printing press, they’d say, “Well, what’s that? Never heard of it”. There’s lots of reporting projects now that are financed by Kickstarter and Indigogo… there’s a lot of people that are financing their investigative journalism that way. There are philanthropic models. We have a half dozen of them… [that] have absolutely no advertising because there is a progressive philanthropist who is willing to spend 10 million on this model. Pretty exciting.

Do you think the digital revolution make our world more democratic?

Cooper: The weapon that is most feared by authoritarian regimes are smart phones, but at the same time they cannot operate without them. In China there are 887 million smart phones. It’s just a matter of mathematics. How long can you sustain that level of control in a society where there’s un milliardo di smartphones?

So are you an optimist about modern society?

Cooper: The evolution of modern society has been extremely contradictory. Before the internet, we solved the major medical problems, we raised the standard of living, generally, but we’ve created incredible inequality: half of the world can’t feed itself, we’ve had mass destruction, atomic bombs, mass surveillance, the mechanization of death. The Internet is now another factor. Whether we wind up being a democratic race or a self-destructive race has nothing to do with the web: it has to do with our desire and our political will.

Your political viewpoint has been described as “contrarian”. Is this why, in your book “Last Honest Place in America”, you write in admiration of Las Vegas?

Cooper: Everything takes all your money: Las Vegas is honest about it. [Vegas] is really the sort of manifestation of a market capitalist society of the sort that Karl Marx predicted would be the result of advanced capitalism. If you want to talk about pure, unalloyed capitalism—it’s Las Vegas. Nothing counts except money. Nothing.

So everywhere else is dishonest?

Cooper: I think very few places in the world are honest. But certainly the richer countries— Europe, the United States, etc.— they cannot be honest because the whole system is the opposite of Las Vegas. It’s based on duplicity. If we go to war we never say it’s for money; we say it’s for some great ideal, or we pretend… [it’s] the sort of hypocrisy that sustains most of the world—it’s universal.

*Edited by Peter Farbridge

Academia is a popular science magazine produced by EURAC and unibz. To get your free copy, please send your name and address to: [email protected]

Click here to read the complete magazine: Academia #70 – Endlich raus | Tutti in campo | Hit the Hills

Stimme zu, um die Kommentare zu lesen - oder auch selbst zu kommentieren. Du kannst Deine Zustimmung jederzeit wieder zurücknehmen.